Recently, I did a powerful exercise in defining what Robert Middleton, of InfoGuru fame, calls an AudioLogo.

Recently, I did a powerful exercise in defining what Robert Middleton, of InfoGuru fame, calls an AudioLogo.

An AudioLogo is a one line description that a business-owner uses in response to the question “What do you do for a living?” The InfoGuru’s short course in defining the best format to use as the response is nothing short of brilliant, and unique.

The result of defining my AudioLogo was that I did some rethinking of my own stock answer to the question, which used to be “I am a management consultant, in the area of strategy and HR.”

As of this month, I am now saying “I help executvies solve really tough people problems that impact their bottom-line.”

Part of this rethinking had me focus on the question of what I do when I design High-Stake Interventions, which happens to be my company’s tag-line.

What separates a High-Stakes Intervention from other possible approaches that can be used to improve a company have mostly to do with the magnitude of difference that is generated. Here is a direct comparison in some specific areas, pulled from my experience working with executives and their teams:

Training

Routine training is delivered off the shelf, meaning that the content is delivered in an inflexible format for a general kind of audience. High-Stakes Interventions, however, are customized for

specific needs pulling from any schools of thought — starting from the ground up with an understanding of the Outcome that is being accomplished. Obviously, this takes more time. The actual design process begins when the designers face the fact that nothing that has been developed will make the difference that it needed.

Coaching

Routine life-coaching involves working with individuals in a long-term relationship, with goals that keep changing as the coachee evolves. High-Stakes coaching tends to be quite blunt and to the point, and relies less on the relationship, than it does on a shared commitment to serve the company’s best interests (usually articulated as a bottom-line concern). It follows no set formula, and involves the willingness to be fired for “speaking truth to power” as some put it. The number of conversations tends to be low, and as little as one or two.

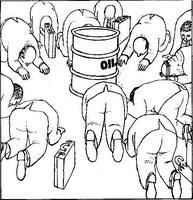

Politics

High-Stakes Interventions always have a political aspect to them, as the intervenors understand that they are engaging the various power interests in the company. New bridges are built as old ones are deliberately forsaken, all in order to improve the odds that the intervention succeeds. Company politics is seen as merely the necessary interplay of powerful people in a company, and an inescapable part of the structure of corporations.

Routine projects either try to ignore the politics behind the scenes, or blame it for all sorts of evils. The team members therefore themselves as victims of the company’s politics, and unable to contribute in anything more than a superficial way.

These are just three ways that I can see clearly at the moment, and while I won’t go into them in meeting someone for the first time, they have helped me look for the kind of work that fits my interests, and my company’s intererst, like a glove.