As a Jamaican employed in an organisation, you are worried about the future of our nation. It appears as if our country is stumbling along, barely keeping its head above water.

At the same time, you are aware of the power of a corporate vision. Why hasn’t someone done one for our 2.8 million people on the island, and the other 2+ million in the Diaspora?

The good news is that something is already in place in the form of Vision 2030. But why isn’t it changing your everyday experience?

The truth is that we need help. The two main things Jamaicans care most about – economy and crime – seem not to have progressed for decades. Instead, we want the hyper-growth of Trinidad-2004 and Guyana-2023. Or maybe even the steady high performance of the Bahamas.

Or perhaps more importantly, we envy the low crime rates of Barbados or Cayman (formerly a Jamaican protectorate.) At some point, we led all these countries in these areas.

Today, we are working hard not to slip into the same zone as Haiti.

If our leading companies can accomplish so much long-term success, why can’t our country, we wonder? While a direct comparison is unfair, maybe there are a few things we can learn from best practices accepted in your organisation.

A Joined Up, Far-Away Future

A “joined-up” future is one that lots of stakeholders contribute to creating. In a company, it means engaging the board, executives, staff, customers, suppliers, regulators, local communities and more.

Shouldn’t our country do the same?

Based on my experience and queries of colleagues outside government…we don’t know that we already have a joined-up faraway future…at least on paper. In fact, the process used to create Vision 2030 Jamaica from 2003-9 is a world-class model. As such, I have shared it at in-person and online strategy conferences as a case study.

Perhaps you recognise the summary statement: “the place of choice to live, work, raise families and do business.” In times gone, it was the tagline of speeches given by the Governor General, Prime Minister, Leader of the Opposition and many others.

But I looked over the recent Budget Debate notes. I struggled to find much of a mention. A Google search didn’t help. Here are a few ways business people at all levels could intervene now to prevent what former leaders of our country seem to be telling us…this is too important to allow it to be eaten up in regular chakka-chakka.

Why the urgency?

With six or so years remaining until we cross the finish line in 2030, we can’t afford to waste a single moment in mid-race. Remember when Miller-Uibo glanced up at the screen and lost her lead in the 400m final of the 2017 World Championships? We are likely to stumble into defeat also as a nation, unless we pay attention to the following.

A Divisive Election – You and I watch the bitter combat underway in the USA. It appears that cooperation towards common goals is impossible. Within a year, our own political parties will try to win the next election by emphasising their differences. This is natural. But it’s the opposite of the intent of Vision 2030 Jamaica. Just imagine if the board of your company were divided into opposing camps. Let’s intervene so that their attention remains on what is most important.

Continuous Inspiration – Your ability to recite our National Pledge and Anthem were picked up as a child. We could elevate Vision 2030 Jamaica to that level of importance, starting with the Forward by Dr. Wesley Hughes, which states in part:

“Today, our children, from the tiny boy in Aboukir, St. Ann, to the teenage girl in Cave, Westmoreland, have access to technologies that were once considered science fiction. They seek opportunities to realise their full potential. This Plan (vision) is to ensure that, as a society, we do not fail them. “

Updated Business-like Measures – How can we know the progress we have made from 2009-2023? Are the measurable results listed in the document beyond reach? Do we deserve an A-? or a D+?

How about fresh, intuitive measures of success which tell us whether or not Jamaica is becoming “the place of choice”? Let’s measure the length of lines outside the US and Canadian Embassies for those seeking permanent residency and how they are growing or shrinking.

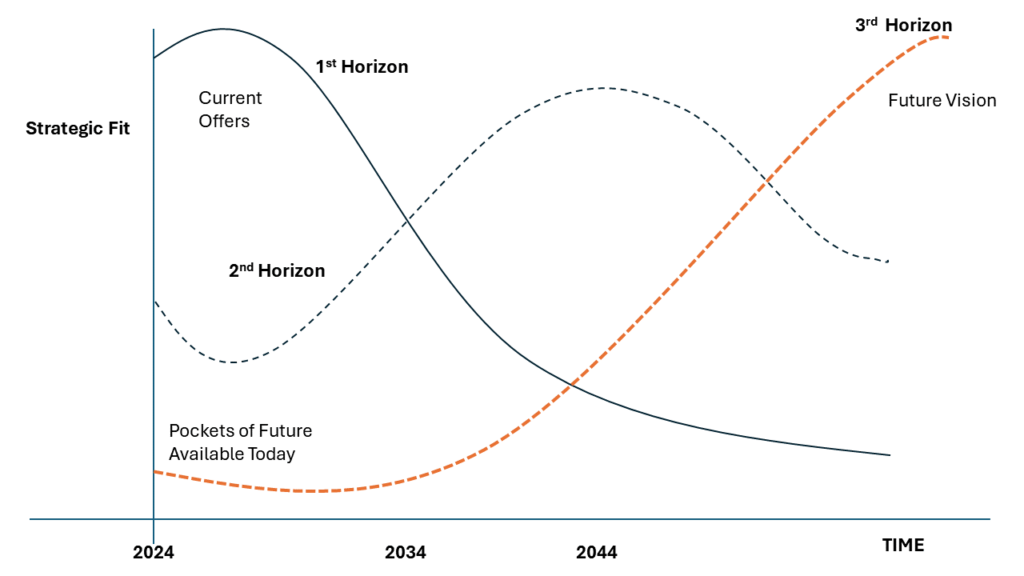

Wheeling and Coming Again – Companies have no problem resetting fresh objectives when the old ones no longer do the job. In business, a strategy that is not working is replaced as soon as it’s found to be lacking.

We can do the same for Vision 2030 Jamaica to keep it relevant. This is the beauty of long-term strategic planning.

An honest read of the original document reveals that certain assumptions about the government’s capacity to lead the effort were unquestioned. Today, after over a decade of effort, we have learned much. For example, it’s hard to argue that the planning done in 2009 was enough.

In summary, while we once led the world in long-term national planning, we aren’t doing the same in the more difficult world of national strategizing and execution. But there’s time.

As the clock ticks down to 2030, things are likely to become more awkward for all of us. As you may imagine, the human tendency is to avoid the issue entirely, hoping it goes away.

That may yet happen. But if we don’t confront the gaps in our initial attempt to create a joined-up, faraway vision, we’ll block our citizens from ever believing in a national vision again.

In fact, it would be better if it were declared null and void, than ignored. At least that would have some integrity and enable us to move on to a better national vision, lessons earned.

Better National Strategic Planning

And that is perhaps the biggest lesson for all concerned. We Jamaicans say that we are great starters, but poor finishers. In other words, we know how to kick things off. But when the going gets tough, we aren’t strong at bringing them to fruition.

Said differently, we don’t know how to keep promises just because we made them.

The point here is that Vision 2030, with some five to six years remaining, puts us in an awkward spot. But that’s a lie. We have put ourselves in an awkward spot.

At some point, we were strong in envisioning great things. Like a company who creates BHAGs, our executive team gave its sacred honour to accomplish a great thing, like the framers of the Declaration of Independence.

However, we haven’t put in place mechanisms sufficient to rescue our current situation. At this rate, we won’t be closer to being a “place of choice” than we were in 2009.

In a company, it’s easier to find individuals or a team of leaders who may hold themselves accountable for a game-changing result. Often, the metrics are clear.

Unfortunately, no such clarity exists around Vision 2030. And given our impending election fever, it may not come from politicians. Instead, it’s time for business to step up and bring sound strategic planning to the accomplishment of the most important outcomes of our national lifetimes.

Let’s inspire each other to intervene so we can have what we already know we want. It won’t happen any other way.