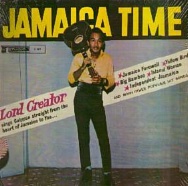

“Jamaica Time” isn’t all that bad, actually.

Once upon a time there was a tourist on a fishing visit to Mexico, who heard about a lake that was well-stocked with edible fish. In a few days, the tourist found himself sitting on the side of the lake, beside a Mexican who was also fishing. He recognized the man from the night before, when he had seen him chatting with his friends over drinks, having a good time relaxing and enjoying their company.

He started chatting with the fellow, in between catches, and as the time passed he realized that he had caught much more fish than he had expected. He was excited, because in all the fishing he had done in his home country, he had never caught this many fish in such a short time.

He asked his new Mexican friend whether this was normal, and he confirmed that, yes, this was always an excellent lake to fish in. He could count on being able to catch enough fish to take to the market to sell each week to meet his expenses, which were not much as he pointed out his modest home on the edge of the lake. He was able to do all this even though he could only afford a single rod and line.

The tourist, who happened to be a successful millionaire and entrepreneur, got even more excited. He said, “Why don’t I help you? I could help you invest in a boat and some equipment, and if we hire the right people, then you could catch enough fish to make some real money!”

The Mexican seemed interested, but a bit confused. “What would I do with all that money?” he asked.

“Oh, then you could really live! You could retire to a nice place in the tropics, and spend time with your friends eating, drinking and fishing each day to your heart’s content. You’d be successful!”

The fisherman sat silently for a while and stared into the sun as it set into the waters of the lake. He replied quietly,

”Why bother? That’s the life I’m living now.”

————————————–

This story made me wonder about coming back to live in Jamaica and work in the Caribbean.

Many Americans think I was nuts to live in the US for even one day, when I had a beautiful country to live in and move back to. Of course, most Jamaicans (and especially those that live in the US) are quick to explain that “all that glitters is not gold.”

However, there is a reason that Americans are willing to save up for years to come to Jamaica, and it’s not only because of the flora and fauna.

Part of it has to with how time is felt and experienced in Jamaica.

My wife gave me a clue by asking me a few times “did you get a lot done today?” and “did you have a productive day?”

Now, this is a normal question to ask in the U.S. It’s so normal and everyday that there is no reason to do anything other than answer directly.

However, it sounded strange here in Jamaica and it drove me to think more deeply about what time is for. It’s clear to me that in the US, time is for getting stuff done. It has utility, and its utility has to do with getting tasks done and producing results. It comes in part from viewing a human at work as a factor of production, and as a tool for work.

Time spent talking with others is seen as something to get through quickly, and pleasantries are necessary evils to be dispatched with as soon as it’s polite to do so.

Here in the Caribbean, however, I sense a very different relationship with time. Instead of an obstacle, time is seen and experienced as a resource, but not as a resource to get stuff done, but one in which the gift of life is to be savored and enjoyed to its fullest.

The Mexican fisherman story illustrates the difference to some degree. Time is seen by the tourist as something to be spent to create a future experience. The Mexican is right to question the logic, implying that the joy of retirement could be experienced in this very moment, and not after it has been “earned”.

In an earlier blog, I mentioned that a friend of mine passed away. He did so while jumping off his boat at Lime Cay, when his head hit a rock and fractured his spine and skull. He died with those he loved, doing what he loved.

That is, he died in the middle of the activity, probably anticipating the feel of the fresh, cool saltwater on his skin at one of Jamaica’s best getaway spots.

In my time working and consulting in US corporations, there certainly was an overriding feeling that the job one was in at the moment could not possibly be a source of enjoyment and excitement. If anyone loved their jobs, they would hide the act from their colleagues, as that was how cynical these environments had become. Furthermore, anyone who was enjoying their jobs was seen as being “drunk on the Kool Aid” (a reference to the Jim Jones cult suicide of 1979.)

In other words, work and the job were things to be endured and suffered through until there was some relief in the form of retirement, which would be spent visiting places like Jamaica, Barbados or Florida – and that’s when real life would start.

The sad thing is that many Caribbean people buy into this logic when they migrate to the US, Canada and England, where they get lost in the material aspirations of these cultures. One day, they too will return to retire in Jamaica.

It seems to me that one is prepared to work hard, and to invest in one’s career, that that might as well happen here in the Caribbean, where time is seen so differently.

Yes, the pace is slower here, but the truth is, that it only seems slower if the goal is to get a lot of stuff done. If, instead, the goal is to savor each and every moment, as if it were one of the few remaining moments, then the “pace” is irrelevant, and instead the quality of the time spent is seen as the variable to maximize over all others.

From my experience, Trinis and Belizeans are particularly good at this.

They seem to understand that the lime, or the time spent with others, is not just important, but to be prolonged as long as possible. I remember spending time in a Trini lime that went for about 5 hours, of just sitting in a circle and drinking mixed drinks (screwdrivers on my part) while eating snacks.

It would never happen in the US, and it would rarely happen in Jamaica. Belizeans and Trinis are willing to get together to just sit, talk and enjoy each other’s company. To say it differently, they actually plan to spend time together to just… enjoy time together, and nothing else. The food is secondary, turning on the television for the heck of it is thinkable, and taking it all to seriously is unforgivable.

Unfortunately, we in Jamaica are becoming more American – more rushed, more impersonal and more mechanical in our interactions with each other. Somehow, at some point we adopted the North American point of view regarding time, and began to relate to “Jamaica Time” as nothing more than being late.

Perhaps “Jamaica Time” has more to do with using time to savor life. Instead of saying “Sorry I’m late” and giving some excuse related to how busy we are, we might say “I’m on Jamaica Time,” meaning to say “I’m late because I was caught up in savoring my life and the people in it.”