A friend of mine from overseas was working in a client bank in Jamaica as a consultant on a major project. He needed to open a local account to do some transactions, and decided to open an account at the local branch of the bank.

A friend of mine from overseas was working in a client bank in Jamaica as a consultant on a major project. He needed to open a local account to do some transactions, and decided to open an account at the local branch of the bank.

He found a branch and tried to open the account, but ran into such poor service that he had to return several times, after which he just gave up in frustration.

He mentioned his experience as a matter of urgency to one of his colleagues in the bank, a vice president.

Her response was: “You mad or what? Why you never come to me first? I would never go into one of our branches to do any of my banking! And deal wid dem people deh? No sah, I only go to the branch manager. Here, next time come to me and I will take care of it for you.”

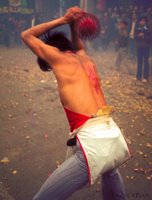

On a quite different occasion, I was eating my lunch while reading the Jamaica Overseas Gleaner, while living in New Jersey. As I turned the pages, I came upon a picture of a mad-man with his head full of live maggots eating his scalp alive.

That was the end of lunch.

I was so disgusted that I felt compelled to call the editor, who I happened to know because I had placed several business ads in the past. The editor was not in, but I did reach the Advertising Manager, who I also knew. Let’s say her name was Mary. She was second in command.

I made my complaint, including the part about the effect the picture had on my lunch. Mary said “Let me tell you something – when I went to pick up this week’s edition from the printer, one of the guys drew me aside and asked me how we could print this. I looked at it for the first time, and that was when I knew that this week’s Gleaner was not going to reach me!!” (In other words, she would not be reading it).

I was flabbergasted… and momentarily speechless and could only recover to ask her, quite weakly, to pass the message on to the editor.

The stories might be different, but the underlying theme is one that I find in too many companies in the Caribbean — too many people doing work they either do not believe in, or do not even like. At times, it seems to me as if all the people who love to serve customers were somehow secretly switched with workers in factories, and on farms, far away from people — while the ones who hate people are stuck in front-line service jobs.

Many Caribbean workers seem to be in jobs they either vehemently or passively dislike. Converely, very few seem to be enjoying what they are doing for a living.

And, we are not very skillful at hiding this fact from each other.

I don’t know yet what the cause of it is yet, but there is at least some lack of care that takes place when people are hired — managers and executives do not seem to be smart about hiring people who even care to use the products and services that the company offers.

In a sports store the workers don’t play the sports. In a shoe store, they don’t wear the shoes. In a health-food store, no-one knows the products because they don’t consume them. In a bank, no-one actually uses the branches if they can help it.

This is just bad for business, and worse for both the employee and the customer, who must now suffer in each other’s presence, while trying to get work done.

I do know that in a tight economy people are just plain afraid to pursue what their heart tells them to pursue. Some use the opportunity to migrate to finally free themselves of these mental chains, but sadly, many are not able to undergo the transformation required. It takes courage to believe in one’s ability, in the face of the culture that is screaming out the stupidity of doing so.

Yet, those who do are the ones who can make up the new Creative Class across our region.

If there is any fault, it lies in our education system, which asks a 16 year old to restrict his or her education to at most 4 subjects for A-levels/CAPE. I will never forget my own junior semester at Cornell in which I did Photography, the History of Art, Government and Philosophy — for full credit — even as I majored in Engineering. Doing these courses (which stand out in my mind as critical to my personal development) sounds bizarre to the Caribbean-trained professional, for whom education has been reduced to a mere instrument — starting at age 16.

This instrumentalism is a travesty, and as I type this I think that there is a certain sadness to see that a decision to pursue training in a career, will end up keeping someone locked in a job for which they have no passion.

One of my favourite authors, Kahlil Gibran says it quite well:

Work:

And what is it to work with love?

It is to weave the cloth with threads drawn from your heart, even as if your beloved were to wear that cloth.

It is to build a house with affection, even as if your beloved were to dwell in that house.

It is to sow seeds with tenderness and reap the harvest with joy, even as if your beloved were to eat the fruit.

It is to charge all things you fashion with a breath of your own spirit,

And to know that all the blessed dead are standing about you and watching.

Often have I heard you say, as if speaking in sleep, “he who works in marble, and finds the shape of his own soul in the stone, is a nobler than he who ploughs the soil.

And he who seizes the rainbow to lay it on a cloth in the likeness of man, is more than he who makes the sandals for our feet.”

But I say, not in sleep but in the over-wakefulness of noontide, that the wind speaks not more sweetly to the giant oaks than to the least of all the blades of grass;

And he alone is great who turns the voice of the wind into a song made sweeter by his own loving.

Work is love made visible.

And if you cannot work with love but only with distaste, it is better that you should leave your work and sit at the gate of the temple and take alms of those who work with joy.

For if you bake bread with indifference, you bake a bitter bread that feeds but half man’s hunger.

And if you grudge the crushing of the grapes, your grudge distils a poison in the wine.

And if you sing though as angels, and love not the singing, you muffle man’s ears to the voices of the day and the voices of the night.

—————————————————————————

Brilliant.

Maybe the new freedom for our people, hopefully including our Creative Class, will be about a personal courage that transcends the culture’s rules.